Now that we have a solid grounding in theoretical syntax, it's time to pause for a moment. The theories I've introduced you to in the last two episodes, while motivated, haven't exactly been ‘from the ground up.’

I will take some of what we've went over for granted, because hundreds of millions of hours of research has been poured into this science since day one, and a lot of correct predictions have been made. For example, I think the existence of features and the existence of some type of lexicon or word list is almost tautologically right – these things must exist, given what we observe about language. Similarly, I strongly believe that syntax can be reduced to its interfaces with semantics and phonology plus Merge.

However, I don't think we should take for granted what types of features language uses, what types of information are encoded in the lexicon and how, and what exactly predicate logic looks like in our brains. So in the next phase of this blog, I'm going to be using concepts from what we've already learned, but we're also going to be throwing out a lot, and starting fresh. Today, we're going to be starting fresh with semantics.

what does conceptual structure actually look like

In episode one, I said that speaking language and understanding language were inverse processes. When speaking, you transition from a logical form (LF) to a sequence of words, and then from there to a sonic signal, or phonetic form (PF). When listening, you do the reverse. This implies that LF and PF are symmetric, and in a sense, they are.

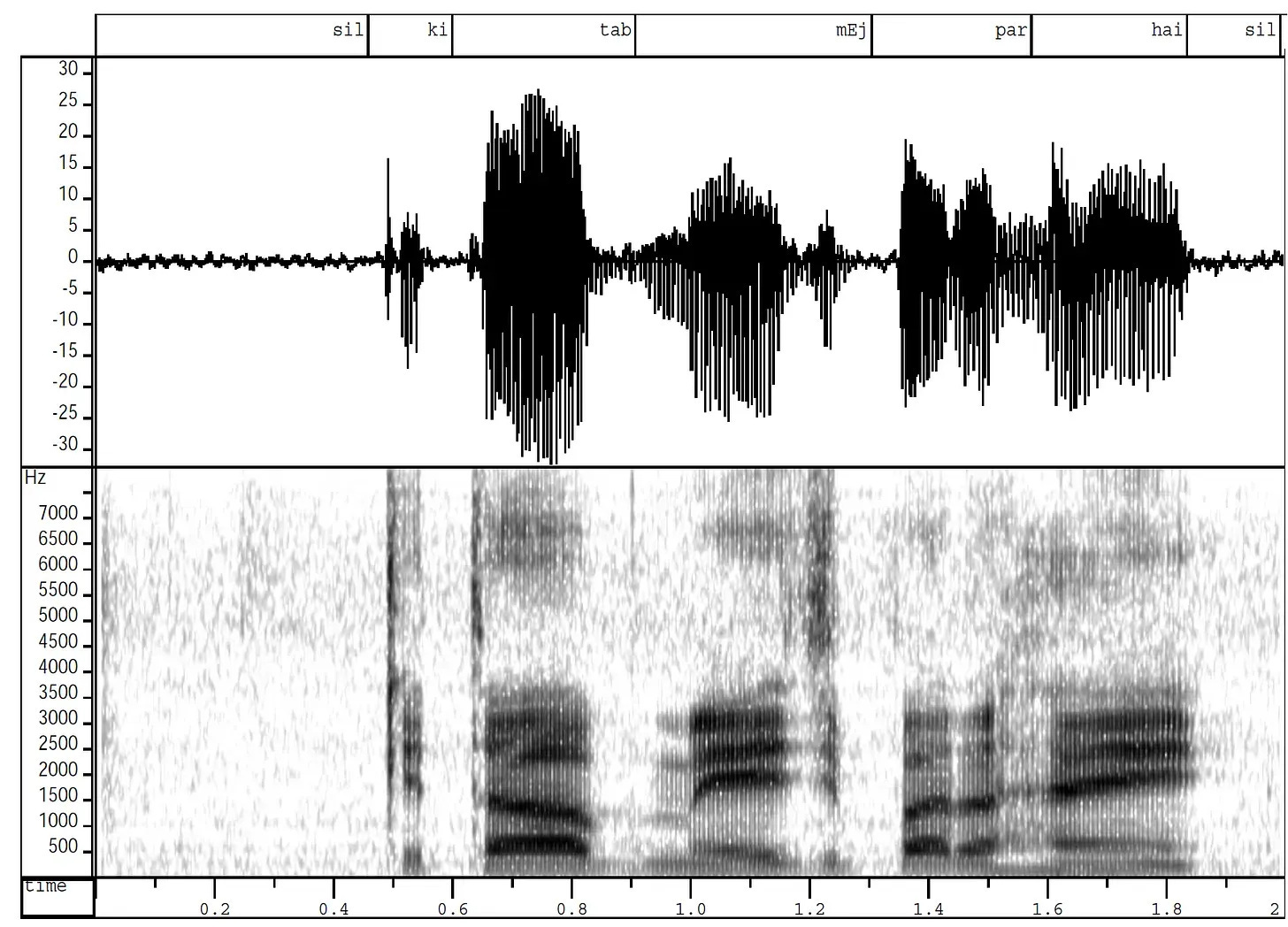

However, there’s one very important thing that is true of PF, but not LF, which was pointed out to me by EM the other day, and that is that we have direct evidence of PF. In other words, we can hear sonic signals, or phonetic forms, and capture them with computers. For any given sentence that someone says, we as scientists know exactly what its PF looks like. It looks something like this:

This is not at all true of LF. For any given sentence that someone says, we as scientists do not know with certainty what its LF looks like. We simply can’t see inside our own heads.

Neuroscience and psychology exist, and sure, we can look at brain scans of humans as they produce sentences, and we know which regions are firing, and maybe we can even find grandmother neurons for specific lexical entries, but that doesn’t really give us an accurate picture of what the logical form of a given sentence is. What compositional logical form looks like.

So how do we figure this out? How is conceptual structure represented in our minds?

narrowing syntax

In episode four we talked about the condensation of syntax. How Minimalism has tried to make syntax “just Merge,” and how everything else in syntax is supposed to have bled in from either phonology or semantics. From the sentence’s LF and PF.

We know what PF is. Maybe all of the mechanisms that transform a sequence of words into a phonetic form and back again are not fully understood—this is what phonologists and phoneticians work on—but we at least know what PF looks like on the outside, and this gives us a pretty good handle on what parts of syntax are actually reflexes of phonology.

This means that if we take out phonology from syntax, and then we take out Merge, what we are left with must be semantics.1

Pengli’s Law: Anything in syntax that is not Merge or phonology is semantics.

In order to sniff out what compositional logical form looks like, we should be detectives, looking through syntax for anything that smells like it doesn’t come from phonology. Once we find something, we should think, “if this property of syntax actually comes from semantics, what does that mean about semantics?”

→ This should be how we figure out what compositional logical form looks like.

conceptual structure from the ground up

But before we start our career as detectives, we should make some predictions. We should try to build our own theory of what semantics might look like from the ground up, just as an exercise.

What should LF intuitively look like? How could we model meaning in our heads?

In episode one, I mentioned that many non-human animals have conceptual structure. Chimpanzees, for example, seem to be able to think of almost anything that humans can think of (at least when considering things that are not man-made). We know this from a wealth of experiments that have taken place in the last half-century showing that chimpanzees have extensive mental maps of their surroundings, can track social relationships between a fairly large group of people, can remember events and apply lessons from the past to the future, can make alliances and fight wars, and so on. Same with cetaceans, elephants, and many bird species. Many animals we wouldn’t normally consider ‘intelligent’ also have some of these characteristics but not all of them.

What’s even more interesting is the evidence we have for how chimpanzees (and maybe other species as well, although I’m not sure) model concepts in their brains. This correlates with the way human babies do it. If you give a toddler a picture of a cow, and ask them to select “another,” they will select a picture of milk more often than a picture of a pig. Similarly, when given a picture of a dog, they will choose a picture of a boy walking, rather than a picture of a cat. This makes it seem like children are primed to model events: the event of a cow being milked, or the event of a boy walking a dog.2

However, when you give a toddler a picture of a cow, and ask them to select “another dax” (where dax is some random, meaningless word you’ve come up with), they will select the pig over the milk, and the cat over the boy walking. This shows that when primed, they also understand objects, or things, or entities. The same is true of non-human animals.

Another ability common to both humans and non-human animals is the ability to put specific examples of a thing into categories of ‘that type of thing’. The ‘platonic form’ of a thing. As we’ve talked about, humans and non-human animals alike have wide-reaching categorical perception. This can also be thought of as the type vs token (single example of a type) distinction. Here’s an example:

1a. John walked his dog yesterday. (event token)

b. walking (event type)

c. John’s dog (entity token)

d. dogs (entity type)

So it seems like humans and non-human animals alike are primed to identify two things: events and entities, in both type and token format. This falls pretty easily into how most ordinary people think about language, in terms of nouns and verbs, except that most people also think about adjectives, or properties, as a part of this set of canonical, basal categories of meaning. So let’s add properties to our list, as well—although stay tuned for another post about why properties are kind of weird.

Linguists say that properties and events are ‘predicated over’ entities. This means that it’s almost impossible for an event or a property to form a propositional statement without an associated entity. Similarly, an entity cannot form a propositional statement without an associated property or event.

I want to be clear about what I mean by propositional, because I know I’ve been using this word a lot. In semantics, I’m going to define propositionality by whether something can be true or false. John walks his dog quietly can be true or false, but the event of walking, or the entity of of John’s dog, or the property quiet(ly), cannot.

Crucially, we talk non-propositionally all the time. If I want Chipotle for dinner, I might ask my mom, “please can we get Chipotle for dinner?” This sentence isn't true or false – it's not propositional – but it's still part of language. Just not a part that can be easily accessed by predicate logic, which usually deals with truth and falsehood. So we’ll be putting it on hold for a while.

To summarize, our intuitive semantics consists of three types of things: properties, events, and entities, and says that events and properties need to be combined with entities, and vice versa, to make a propositional statement.

evidence from syntax

Now let’s think about things in syntax that are not present in phonology, and not due to Merge.

Why do (2a-b) sound totally fine to us, whereas (2c-d) sound weird?

2a. Twas brillig, and the slithy toves did gyre and gimble in the wabe.

b. John and Mary ate applesauce together.

c. *Brillig and twas, toves slithy the gyre did gimble wabe in the.

d. *Ate applesauce John and Mary together.

The asterisks in front of (2c-d) signal to linguists that these sentences are ‘ungrammatical.’ Importantly, grammaticality judgements are NOT based on concepts of ‘proper grammar’ or ‘good writing’—they are based on what sentences individuals spontaneously produce, and what sentences individuals think ‘sound weird.’ The grammaticality judgements of one person will almost inevitably differ from those of another person in some small way or another; however, most speakers of a given language or dialect will agree on grammatical judgements for the most part.

For some reason, (2a) sounds fine to me, even though I have no idea what it means, whereas (2d) sounds bad, even though I know exactly what it means. This cannot be explained by phonology, and it cannot be explained by Merge—at least, not by Merge alone. There must be some non-obvious RULES to Merge—to which things can Merge when, and which can’t. Given that we are trying to narrow syntax, these must come from semantics. (We’ve already discovered one potential solution to this with features.)

Furthermore, how exactly do we go from a hierarchical sequence of words (syntax tree) to a logical form? How do the logical forms of each word combine to create a single logical form for the entire sentence/tree? How do they create propositional meanings, and what determines which meanings are formed?

Some (in fact, most) sentences are ambiguous in ways that are certainly tied to how meaning is combined:

Constituency Ambiguity. The sentence John saw the elk with binoculars can be interpreted in two different ways, depending on whether you think John has the binoculars or the elk does.

Scope Ambiguity. The sentence Every student read a paper can be interpreted in two different ways, depending on whether you think everyone read the same paper, or there was a different paper for each student.

For both of these cases, the same sequence of words can be interpreted in multiple ways. Syntax tells us that this is because the structure of their trees differ. But why does the structure of their trees differ?

Basically, we need a theory for how trees put together the logical forms of their terminal nodes to create specific meanings. This theory will be our compositional semantics.

note that this is *a* theory. not the most well researched theory or the most accurate theory. just the one david came up with in his backyard for these reasons. david might sound confident but he is not. check out the table of contents here.

A great relevant quote from Sean B Carroll in Endless Forms Most Beautiful (p111): “In cosmology, biology, as well as other sciences, the existence of particular entities is detected either directly, by observation, or indirectly, by observing the effects on other entities that are more easily visualized or measured.” (= dark matter and regulatory genetic switches)

This is from Markman and Hutchinson, 1984. Sorry for not citing things as much as I should in this blog! Hopefully you can google things, and if you can’t find the source for something and want it, just let me know and I’ll find it for you :)

This was so interesting!! Thank you